“Some say the world will end in fire, some say ice. From what I’ve tasted of desire, I hold with those who favor fire. But if it had to perish twice, I think I know enough of hate to know that for destruction, ice is also great and would suffice.¹”

What’s a More Significant Risk, Inflation or Deflation?

In this poem, Robert Frost posits the destruction of the world will be due to either intense passion or bitter hatred, i.e., fire vs ice. Too often, we tend to oversimplify our analysis to assume that only one power or risk is present at any time. In today’s current market environment, we see the forces of inflation and deflation are at work. Central bankers are and should be concerned about price stability, but too many assume that price stability is only a one-way street.

Today, we are solely worried about inflation. The consensus believes that a tight labour market will create Inflation. China is opening; that’s inflationary. The U.S. Census Bureau finds 1 million new citizens; that’s inflationary.

If history has taught us anything, however, price stability is a two-way street involving inflation and deflation. How quickly we forget the dominant narrative of the global financial crisis or the prevailing history concerning Japan since the late 1980s—deflation and the inability of monetary policy to get inflation to approach the 2% target. How quickly we forget that the Federal Reserve altered its policy to Average Inflation Targeting. It recognized that extended periods with the economy below the 2% target were undesirable and increased income inequality. If one takes a longer time horizon, inflation is finally above 2%, and the Fed Funds and the Bank of Canada overnight rate are substantially off the zero bounds, providing dry powder in the future to support the economy if needed in a cyclical downturn. In a way, central bankers have achieved their desired goal that existed pre Covid-19, but will they snatch defeat from the jaws of victory?

Many argued in the past that deflation is a greater risk to the economy because of its potential to cause a widespread economic depression. Deflation occurs when prices of goods and services fall, and this has the potential to be a significant disruption to how businesses and people operate. When prices fall, companies face lower demand for their products as consumers now have less money to spend. Reflexivity implies that this leads companies to cut costs by reducing their workforce and scaling back operations, further contributing to the deflationary spiral. How quickly many forget that the events of the Great Depression were caused by the Fed aggressively raising rates into a high leverage, slow global economy. In 2002, then-Governor of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, acknowledged publicly that the Fed’s policy mistakes contributed to the “worst economic disaster in American history²,” echoing the conclusion by Anna Schwartz and Milton Friedman in their book, A Monetary History of the United States, 1863-1960.

In the late 1990s, Barton Biggs used Robert Frost’s poem to provide context and frame his intense debate with Steven Roach on a more significant risk, inflation or deflation. Mr. Biggs argued that deflation was a more substantial risk while Mr. Roach, anchoring off the Phillips Curve, offered the counterargument. While the world today is focused on fire (inflation), as it was in the 1990s, ice (deflation), the loss of pricing power, overcapacity, and secular stagnation await us if the central banks overtighten. Furthermore, if the current communication strategy of central bankers is any indication, investors need to prepare for them to overtighten once again.

The tension between inflation and deflation has been a critical element of business cycles throughout history. Investors and policymakers need to consider both concepts to assess the environment accurately. To be sure, inflationary/deflationary forces are never permanent; they come and go as economic fashions. But any policy that skews too far to either side of the debate will eventually prove wrong and understanding the tension between the forces of inflation and deflation is essential. Before COVID-19, we lived in a world characterized by secular stagnation, with interest rates at zero-bound in North America and negative in Europe. If we are not careful, these same conditions await us.

The Long-Term Deflationary Risk

COVID-19 strengthened foundational deflationary forces (debt/GDP, digitization, demographics, and globalization), and the unintended consequence of aggressive overtightening will be another deflationary crisis. Central bankers up until recently have ignored the threat of deflation (Chair Powell did mention dis inflation over 10 times in his latest Q&A), being solely focused on the belief that excessive job openings (JOLTS) and historical unemployment are about to unanchor inflationary expectations. I have suggested that these fears, while noble, are misplaced. Taking the current report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics at face value, one can conclude that there is no evidence that historically low unemployment and historically high job vacancies contribute to inflation. As now former Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve, Lael Brainard stated in her January 19, 2023, speech: “…despite constrained supply, wages do not appear to be driving inflation in a 1970s-style wage-price spiral.³”

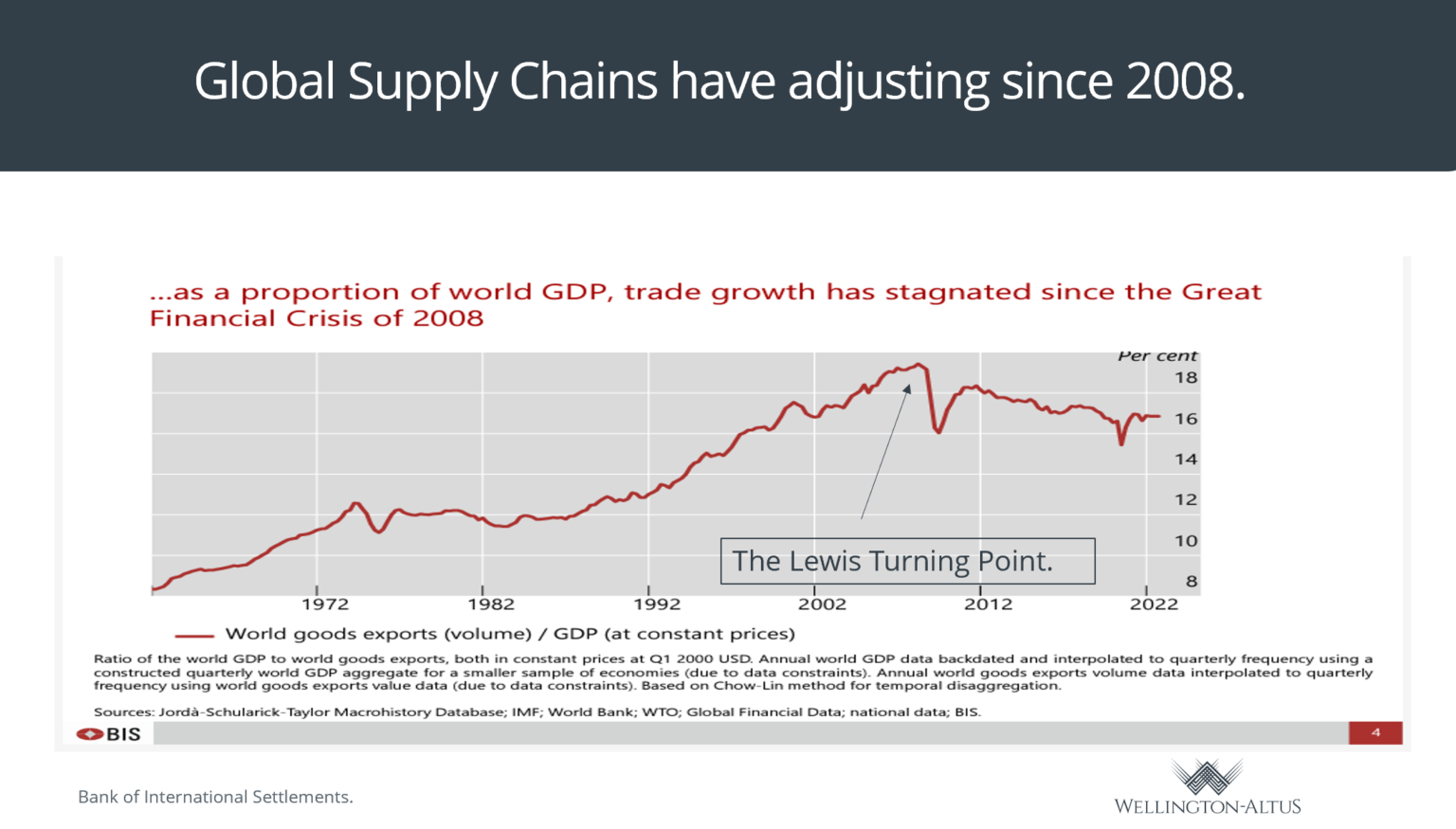

Debt to GDP has increased dramatically. The closure of the global economy has accelerated the evolution of the worldwide economy toward digitization. Population growth continues declining in the western world and has gone negative in China. Additionally, the development of the global supply chain continues to evolve, as it has been since China hit what economists refer to as the Lewis Turning Point – the point upon which an economic advantage no longer exists. The era of excessive commodity demand driven by urbanization is over. As a result, deflationary forces are stronger today in China than in past decades.

Investors need to be concerned that many have misdiagnosed the root causes of our current inflationary episode and wrongly anchor off the 1970s inflation spike and the action of then-Fed Chair Paul Volcker. The misguided conclusion is that the only way to defeat inflation is through a recession. Contrary to the current Wall St narrative, the recession in the early 1980s did not beat inflation. Former Fed Vice Chair Alan Blinder’s research in 1982⁴ definitively concluded that: “…many people continue to this day to give credit to the recession for breaking the back of double-digit inflation whereas it was, in fact, the waning of special factors that did the trick.”

Today, the special forces causing inflation are two exogenous shocks and a level of fiscal policy expansions not seen since WWII. As in the 1980s, inflation will dramatically fall once these factors begin to wane. The decline in inflation began before the historical hikes in interest rates started to take effect. It is a false premise that interest rates need to be hiked to an extreme level to cause a significant increase in unemployment and cause a recession because that’s what Volcker did to defeat inflation. This narrative is not supported by the facts. One can easily make the argument that Paul Volcker is a false prophet. As in the 1930s, the risk that no one is talking about is a debt deflation credit crisis. As Mr. Biggs suggested, ice will do more damage to the economy than fire. As Mark Twain instructs, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for certain that just ain’t so.”

Current Long-Term Permanent Inflationary Risks

The longer-term inflationary risk today results from fiscal policy rather than wages. These fiscal inflationary pressures are caused by the desire of some to implement policies, for example, to reduce income inequality or greenhouse gases, irrespective of their effects on inflation. Can these policies be implemented in a non-inflationary way? As Nobel Prizewinning economist, Thomas Sargent theorized, “permanent high inflation is everywhere and always a fiscal phenomena.⁵” With the IMF reporting that global debt has reached 256%, one wonders how long the global economy can withstand high-interest rates.

In the late 1960s, bowing to political pressure, President Johnson’s Great Society policy introduced dramatic social reform, disregarding its long-term inflationary effects. Monetary policy cannot counteract the extreme forces of fiscal policy, which is why we may have been too harsh on central bankers that came before Paul Volcker. Could Paul Volcker have been able to counteract the long-term inflationary pressures caused by NASA’s quest to reach the moon, the Vietnam War, and the Great Society? I say no. Mr. Volcker is not the prophet many make him out to be. An excellent central banker, yes, but with the good fortune of being at the right place at the right time.

Today, many try to frame the debate with the context that the Fed wants to avoid making the same mistakes they did in the late 1960s and early 1970s. If that’s the case, we need an honest and transparent recognition that fiscal policy threatens long-term inflation more than wage increases and a tight labour market. If not, monetary policy could be rendered impotent. Risks of unfunded entitlements, net zero, healthcare, and income inequality need a pragmatic solution that balances adoption and mitigation. At the same time, the ability to minimize structural inflationary effects on the economy. For example, the implementation of a policy that detrimentally affects the fertilizer industry will cause food prices to rise. Likewise, raising the minimum wage may cause prices in restaurants to increase.

The Fed’s response to COVID-19 was to use sector 13-3 of the Federal Reserve Act to create $4.5 trillion for the Treasury to inject through social programs to support the economy through the pandemic. This injection was as large as the fiscal policy response to WWII but implemented in half the time: the result was inflation. With extreme debt levels, it will be only a matter of time before the credit markets push back. Yes, the return of the bond vigilantes should not surprise. But if fiscal responsibility does not return, investors need to prepare for an era of higher interest rates and a financial crisis with the debt bubble finally popping, ushering in a new deflationary era.

In this instant gratification, group-think world, we need to remember that the thesis Chair Powell and Tiff Macklem anchored from in early 2022 was that the private sector, historically low unemployment, and job openings would lead to wage growth. Mr. Powell and Mr. Macklem are softening their stance on inflation while simultaneously recognizing the risk to the downside if the policy overtightens and ignites a debt deflationary downward spiral. The fight over inflation is not over, but if policymakers look ahead 18 to 24 months, they can easily paint a plausible narrative where deflation and secular stagnation episodes take hold.

What Should Investors Do?

Investors should expect the heated debate between inflation and deflation (fire and ice) to take center stage as the year progresses. Our base case is that inflation will continue to decline. In this environment, stocks and bonds should continue to appreciate, with annualized non-seasonally adjusted CPI from July 2022 tracking at 1.71% in the U.S. and 1.026% in Canada. Inflation is slowing in a structurally tight job market. An occurrence many proclaimed could never happen. A recession may not be needed to tackle inflation, just as in the 1970’s. With deflationary forces sitting in the wings, the more that central bankers continue to raise rates, the higher the probability of a significant deflationary event.

With the Republican control of Congress, and a budget ceiling debate on hand, there is a strong possibility that fiscal policy will become less inflationary. There are early indications that central bankers get it and thus recognize the risk to overtightening. As the year progresses, we expect the data to become more substantive in supporting the belief in deflation, secular stagnation, and a decline in interest rates. True, we live in an instant gratification group-think world, where narratives change as quickly as the positioning of day traders. With that, the debate between fire and ice will take center stage. Significant deflationary pressures built up in the pipeline, such as housing, should provide enough solid data for the central banks to pause and evaluate. Price stability is slowly, before our eyes, evolving into a two-way street, where the tension between the forces of inflation and deflation counterbalance. An environment where fire and ice cancel each other out sets the stage to a continuation of our secular bull market into the end of the decade.

1. Fire and Ice by Robert Frost | Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44263/fire-and-ice ;

2. Ben Bernanke, “On Milton Friedman’s Ninetieth Birthday,” Remarks by Governor Ben Bernanke at the Conference to Honor Milton Friedman, University of Chicago, November 8, 2002. ;

3. Leal Brainard, Staying the Course to Bring Inflation Down, Presented at the University of Chicago, January 19, 2023. ;

4. Alan S. Blinder, The Anatomy of Double-Digit Inflation in the 1970s. National Bureau of Economic Research, 1982. ;

5. Sargent, Thomas J. (2013), “Letter to Another Brazilian Finance Minister. ”Republished in Rational Expectations and Inflation, 3rd edition: Princeton: Princeton University Press